BACKGROUND: On September 14, hundreds of workers at the building site of Istanbul’s new airport – which will open on October 29 and which will be the biggest in the world – went on strike to protest their working conditions after an accident at which several workers were seriously injured. The protesters demanded improvement of transportation, accommodation and working conditions, and that the participants of the protest were not laid off.

The authorities took swift action against the workers. Hundreds were rounded up at a nightly raid by the gendarmerie and detained. 24 were arrested for “damaging public property,” “violating laws on assemblies and rallies,” “resisting police” and “violating freedom to work.” Meanwhile, protesters that had assembled in Istanbul’s Kadiköy district in an act of solidarity were dispersed by the police. The hashtag supporting the workers, "we are not slaves" (#köledegiliz) was a trending topic on Twitter.

It is not a coincidence that the first clash between the AKP regime and labor took place at the building site of the new Istanbul airport. The construction sector has been the engine of the Turkish economy, accounting for up to 20 percent of the country’s GDP growth in recent years, and employing around two million people. But the construction industry is also notorious for its dismal safety records; it accounted for almost a quarter of last year’s work place deaths. The number of job-related deaths in Turkey reached 2,006 in 2017, according to The Workers’ Health and Work Safety Assembly, a Turkish NGO. That figure was up from 1,970 deaths in 2016. The construction of the new Istanbul airport accounts for a significant share of the death toll. According to the Turkish Labor Ministry, 27 workers have been killed at the airport worksite since construction began in May 2015. However, unofficial reports put the death toll in the hundreds.

Part of the problem is subcontracting system. Subcontracting is widespread in the construction industry, and working conditions are typically worse when the employer is a subcontractor. Many subcontractor companies withhold worker benefits such as severance compensation and paid annual leave. The workers are usually paid minimum wage and indeed even below the legal minimum wage.

The AKP’s popularity among workers has rested on two pillars: a growing – debt-driven -- economy and the failure of the social democratic opposition to address the economic problems of the working class and low-income groups in general.

Turkey’s ruling party has been a major beneficiary of the Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing (QE) program and rock-bottom interest rates. QE was launched in December 2008, in an effort to prop up a battered financial system. For nearly a decade, interest rates remained at historically low levels.

As a result of quantitative easing, developing countries have enjoyed a decade of cheap money. For years, as elsewhere, economic growth in Turkey was fueled by cheap credit. Corporations took large loans in dollars or Euros. Debt driven consumption boom fueled economic growth. Personal loans and credit card debt has also played a significant role in enabling the consumption boom.

The Turkish working class has received its share of benefits of the growth, along with other social groups, even though the AKP’s neoliberal economic policies have disproportionately benefited the wealthiest in society. Real wages have nonetheless risen palpably in the period of QE. Taking 2003 as the base year, between 2003 and 2018 the index of Turkey’s net minimum wage rose to 709 from 100. That compares very favorably with the index of headline CPI inflation number, which rose to 357 within the same period.

The debt-driven economic growth has created industrial boomtowns across Turkey. The AKP has carried not only the booming industrial cities in Anatolia, the conservative heartland, such as Bursa, Gaziantep, Denizli and Manisa; the party has also won big majorities in the new industrial centers of Thrace, the European region of Turkey that had traditionally been a stronghold of center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP). The annual population growth rate of these industrial towns in Thrace between 1990-2016 has been shockingly high, at 508 percent for Çerkezköy and 200 percent in Çorlu.

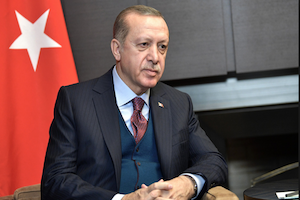

IMPLICATIONS: The CHP has a responsibility for the working class’ right-wing turn. The center-left opposition party has given priority to middle class lifestyle issues, particularly the defense of secularism, at the expense of labor and social issues. Naturally, the peasants-turned-workers from the culturally conservative Anatolia heartland have kept their original party sympathies. When politics is reduced to lifestyle issues, the working class has easily identified with AKP leader and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, his neo-liberalism notwithstanding.

The unnoticed, dark side of Turkey’s economic boom was always the repression of labor, and conditions worsened with the state of emergency after the coup attempt 2016. The scope of strike bans was expanded to the banking sector and to urban transportation. Several strikes, involving thousands of workers, were banned with reference to the state of emergency in place since the coup.

In a recent meeting with the managers of the foreign companies operating in Turkey, President Erdoğan went out of his way to underscore how business-friendly his regime is: “We enforce emergency laws for the benefits of the business community,” he said. “So, let me ask: have you got any problems? Any delays in work? When we come to power, the factories faced the risk of strikes. Remember those days! But now, by making use of the state of emergency, we immediately intervene in workplaces that are threatened with strikes.” Indeed, according to The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), Turkey is now among the ten worst countries for workers.

As long as the economy was thriving, the workers seemed to have acquiesced to the curtailment of their rights. But every fairy tale has an end. And Turkey’s fairy tale ended with the U.S. Federal Reserve’s decision to end quantitative easing (QE) in 2014.

It was a well known fact that the end of QE would mean a fall in economic growth in emerging markets if no structural reforms were undertaken. The credit ratings agency Standard & Poor’s had already warned in 2014 that the boom in consumer credit had become a serious risk for the Turkish economy.

The anticipated crisis finally hit Turkey this year. Turkey's currency is in free fall, with rising inflation. Wages have not kept up with the hike in inflation, so the impact has already been profound in terms of the cost of living. With the rapid depreciation of Turkish lira, the minimum wage in Turkey dropped from $423 to $259.

The currency crisis has brought the country’s construction boom to a stop, with even some of Erdoğan’s favorite mega-infrastructure projects being suspended or scaled back. Along with infrastructure projects, housing construction has reached its limit, and more than two million apartments are unsold.

It is highly probable that the worker protests at the Istanbul airport construction site are only the beginning. The drop in the Turkish lira and the rise in inflation are already straining the relationship between workers and the government and companies. The monthly poverty threshold for a family of four increased by more than 20 percent in the past year to reach 5,904 Turkish liras ($957) in August, according to the Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions (Türk-Iş).

The minimum wage in Turkey is 1,603 liras ($259) per month as of 2018. Türk-Iş calls for a 25 percent hike in the minimum wage while the Revolutionary Trade Unions Confederation (DISK) demands a 50 percent pay hike. Yet it will be impossible for the employers to accommodate such demands as they are in the throes of a vicious cycle of negative growth with diminishing sales and falling profits.

Turkey is also on the brink of a tsunami of bankruptcies. Several companies, including three well-known brands, have already filed for bankruptcy protection due to their "problems with short-term payments" linked to the currency crisis. Economists forecast that the Turkish economy will fall into recession in the last quarter of 2018 and in the first half of 2019. The fall of the Turkish lira and the rise in unemployment will further fuel labor discontent. A winter of discontent is on the horizon.

CONCLUSIONS: There is a strong relationship between economic performance and political outcomes in Turkey. Yet it is still not a foregone conclusion that the rise in inflation and unemployment will bring the love affair between the Turkish working class and Erdoğan to an end. The upcoming local elections promise to a difficult ordeal for the AKP, but there is on the other hand no viable, leftist alternative to conservative rule.

The center-left CHP is convulsed by an internal power struggle since the presidential election in June between party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu and Muharrem İnce, the party’s presidential candidate. And besides, the party has nothing new to say to the workers. The lack of a strong social democratic alternative could give Erdoğan’s conservative party another lease on life despite a deep economic crisis.

AUTHOR’S BIO:

Barış Soydan is a columnist for the Turkish news site T24. He has been editor-in-chief of TurkishTime, of Power, of Turkish business magazines, and managing editor of the daily Sabah.

Picture credit: kremlin.ru accessed on September 24, 2018